Design the Perfect Simulation Research Study in 6 Easy Steps

March 8, 2022, 11:18 a.m.

As a statistical advisor, I am often asked to assist in the development of simulation-based research studies. Usually, the researcher is very excited about a new simulation they have developed, and wants to do a research study to show how awesome it is. However, simulation research studies have some peculiar requirements, and getting it right can take some careful planning to avoid wasting time and effort.

Let's discuss the (fictitious) student Ariel Wang. Ariel is a PhD student working in Critical Care Medicine. She has been working for several years developing a high-fidelity simulation that her department has found very useful in teaching resident physicians about the use of various types of airway strategies. In particular, she finds the simulation is excellent for teaching the advanced skills of video-laryngoscopy in crisis situations. Ariel would like to conduct a research study on her simulation.

Ariel is unsure how to design simulation research. Her initial plan is to take a group of residents, expose them to her simulation, and then have them write a multiple-choice test about how to manage a difficult airway. She hopes to prove that her simulation is a good way to teach advanced airway skills.

In various similar forms, this is a common first idea for many researchers in simulation. However interesting this initial plan, it is not strong as a research protocol. It is vague and contains a number of biases. Ariel needs some help to develop her initial idea into the perfect simulation research study.

Getting Started

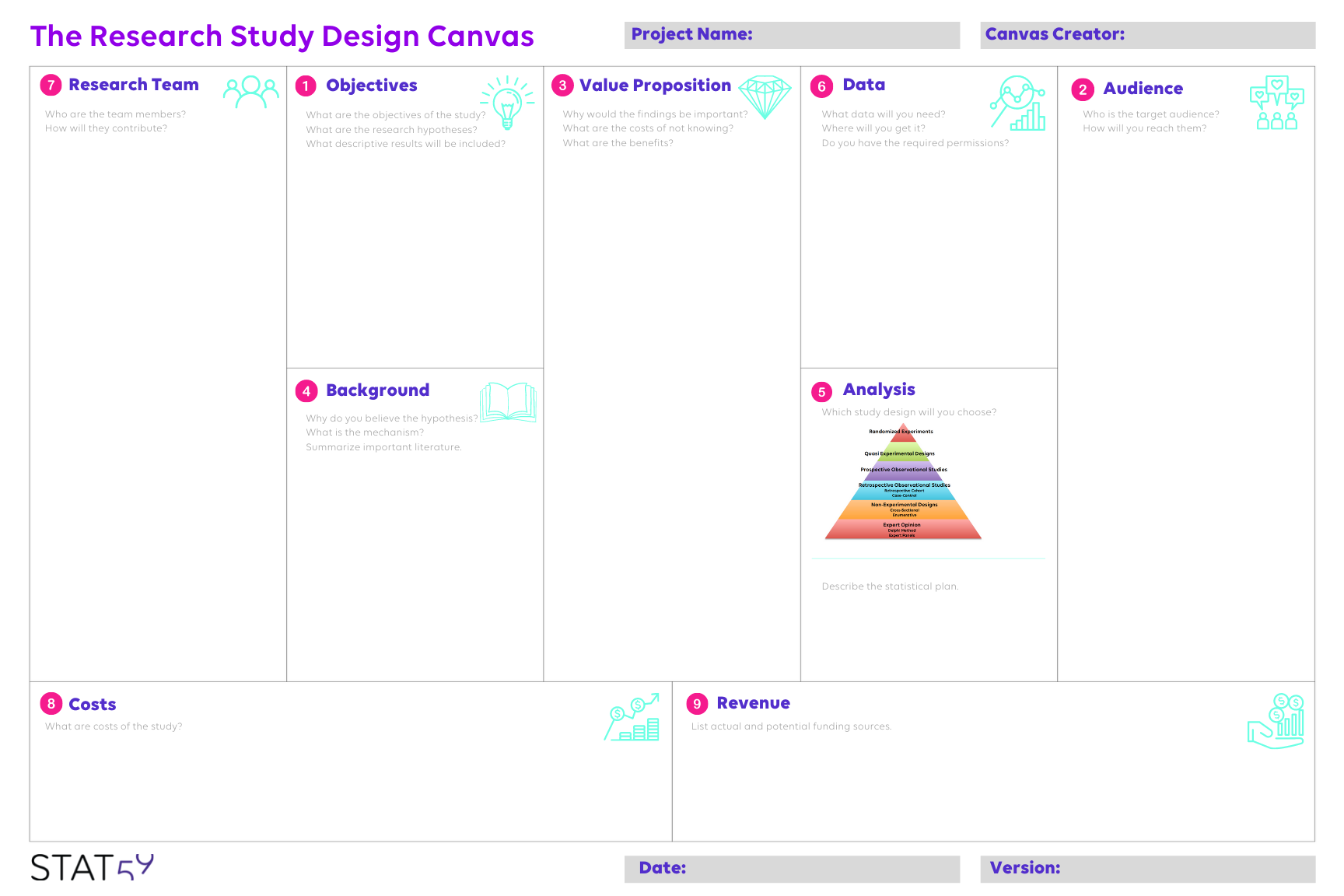

To start, Ariel will download a copy of the STAT59 Research Study Design Canvas. She prints it onto a 24 x 36 inch poster, hangs it on a wall, and finds a bunch of small 2 x 2 inch post-it notes. She gets her small group of co-investigators in the room, and gets ready to work.

She will follow six simple steps to transform her vague idea to the perfect simulation research study.

1. Focus on a Single Validated Outcome

Box number 1 on the canvas, and the most important part of any simulation study is the Objectives. Focusing on a single validated outcome is the ideal way to develop a powerful research study.

For Ariel, in her initial study design, the objective is vague. Ariel wants to prove her study is effective for teaching airway skills, but, effective in what way? Her initial idea, to test participants' knowledge using a multiple-choice test, is full of bias. If she develops the multiple-choice test, she can easily bias the study in any directions she likes. For instance, she could make a test too difficult for anybody to pass. Perhaps a test full of topics that are not even addressed in the simulation. Conversely, she could make a test that is too easy. Then, when the participants get very high marks, she could claim it was due to the simulation.

To improve her study, Ariel should focus on a single validated outcome. For instance, she could focus on evaluating the time it takes to perform an intubation and compare it to a published standard. Or, better yet, she could have a comparison group that did not practice on the simulation and see if there is a difference in the time to perform an intubation between the group that received training and the group that did not. Ariel consults a professional librarian to help her find a published and validated test to evaluate simulation performance. She finds the Ottawa Crisis Global Rating Scale (Ottawa GRS) and decides to use this as her scoring tool. Her final study outcome will be the difference between GRS scores attained by the two groups during a simulated airway crisis. She will compare groups that have received the standard residency training in intubation on patients in the operating room (control), versus those who have the standard training and additional simulation training (intervention).

On a sticky note, she writes the single primary objective of the study and places it in box 1 of the study design canvas. She also writes the study hypotheses:- On one sticky note, she writes the researcher's hypothesis: Groups trained on the simulator will perform better in crisis resource skills than those who are not trained on the simulator.

- On another note, she writes the null hypothesis: There is no difference in GRS score between the intervention and control group.

- Using another note, she writes the alternative hypothesis: There is a significant difference in GRS scores between the control and intervention group.

Finally, she uses some additional notes to describe some supplemental descriptive outcomes. These are outcomes that she will include in the results and discussion of her project, but that will not be part of formal hypothesis tests. Her descriptive outcomes will include how long it takes to perform the intubation, whether the group uses conventional or video laryngoscopy, and the participants' satisfaction rating on a short post exercise questionnaire given to the participants.

2. Write for a Specific Audience

Box 2 of the study design canvas invites the researcher to carefully consider the Audience. Defining the audience for your study is critical. The research team should carefully consider the question: "Who cares?"

In my opinion, the road to hell is paved with research papers that have no audience. I have had the honor of authoring several papers with no target audience myself. As a thesis advisor, I see this very commonly among students. For instance, among students working on theses in disaster medicine, one of the most common topics is to assess the knowledge of disaster medicine among clinical workers at their site. This type of study can take many forms, including assessing skills at triage, familiarity with the disaster plan, or general disaster medicine knowledge. But, in the end, all of these studies suffer from the same problem: "Who Cares?" You could also test the general population's knowledge of calculus, but again, who cares?

Ariel feels that the results of her study will be important to medical educators in Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Emergency Medicine. She feels her study will be particularly relevant to residency training programs in smaller hospitals, or in areas with a shortage of experienced teachers. Next, she chooses a target journal for publication. By looking at the journal's Instructions for Authors section on the website, she can design her study from the outset to meet the journal's criteria. This strategy avoids any last-minute surprises at the submission stage.

3. Study a Concept: Not Your Simulator

The next step in the research design canvas is box 3: the Value Proposition. What value is this study for others? How does it contribute meaningful information that others can use?

The number one piece of advice I can give for any simulation study is to study a concept, not on your Simulator. One of the most exhilarating experiences to anyone who works in this field is designing a new simulation and seeing it being born and growing in front of you. Perhaps the most common study design I am asked to comment on is this: A researcher develops a teaching simulation. He gives a pre-test to a group of participants, and then, after the participants train on the simulation, gives them a post-test. By comparing the pre and post-test results, he exclaims that he has proven that his simulation is effective for training. The problem with this study is the poor value proposition. Of what value is this information? Firstly, other groups are unlikely to want to duplicate your simulation exactly, so, proving the effectiveness of your simulation does not really help them much. Secondly, the test outcome chosen, increase in test score, is not especially valuable. It seems quite obvious that test scores would increase: it is the fundamental basis for the philosophy of teaching, and relatively unexciting. We could test a Grade 3 class in mathematics at the beginning of the year and then again at the end of the year. Although surely test scores would improve, it hardly qualifies as high-value research.

In Ariel's initial study, she is setting out to prove that her simulation is effective for teaching. She is (rightfully) proud of her simulation and wants to show the world how awesome it is - a great Instagram post, but not a great academic article.

To improve the value proposition of her study, Ariel decides that she will want to emphasize that simulation training in addition to standard training will give superior skills in crisis resource management. She gets out her sticky notes. On one note, she writes, "residents can practice crisis management without endangering patient safety." On a second, she writes, "ensures all residents have exposure to crisis management even if their residency training is short." A third note is written to say "consistent training for all residents." Taking time to consider the value proposition early in the research study design process will ensure that the study remains focused on truly solving a problem. And, as a bonus, sorting this out here on the Research Study Design Canvas will make writing the final report much more fluid.

4. Get a Librarian to Help

Box 4 on the canvas is Background. Writing the background - or introduction - to a scientific paper, poster, abstract, or even LinkedIn article can be tricky. We want to make sure that we provide adequate but not excessive background, and answer the question "Could this possibly be true?"

Basing a study on simulation often makes writing the background tricky. All of us have the risk of becoming a victim of Hybris and believing that our simulation is wholly unique and nobody else has ever developed anything like it. Frequently we do a quick literature search, and, unable to find any relevant publications, conclude that our instincts were correct We go on to write our research study, assuming there is no literature that needs to be considered. More likely, however, is that the literature search was simply inadequate.

A heuristic that I follow is to always get help from a professional librarian if I am unable to find suitable background literature. If you are not a professional librarian, I highly recommend you do the same. It is tempting to believe that an online course or a YouTube video on how to use PubMed can make you into a professional librarian, but this is simply not true. If you feel that you are truly working on a valuable project, is it not worth a few hours of your time to get a professional to help?

Ariel consults with a librarian at her University. Through a careful literature search, they find that other researchers have studied the use of simulation to train crisis resource skills in different scenarios: both medical and nonmedical. She finds good evidence that this concept is true in many areas, but has not been extensively studied in intubation skills. She then writes the references on sticky notes and places them on the canvas. These are the articles she will cite when she writes the introduction and discussion of her paper.

A quick pro-tip. Make sure to refer to the audience when thinking about the background. The level of sophistication of the reference articles must match the target audience.

5. Plan In Advance for a High-Quality Analysis

Setting the Analysis is step 5 on the design canvas.

Choosing the methodology can be tricky, but remember that high-quality studies always set down the statistical methodology before the data is obtained. A helpful paradigm is to aim as close to the top of the Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) pyramid as you can reasonably attain. It entails a careful balance of cost versus sophistication. The statistical analysis plan also involves selecting a validated and reliable assessment tool.

I have seen, unfortunately, countless simulation studies that were ruined simply because the researchers did not think carefully about the study design before collecting the data. Often I am called in as a statistician to pick up the pieces and rescue the study at the publication phase. However, elementary errors in data collection frequently have huge consequences that cannot be fixed. For instance, one group I worked with designed a simulation study but did not carefully discuss with a statistician the randomization plan before collecting data. The participants were randomized based on their last names. When submitted to the journal, a peer reviewer very correctly commented that group assignment by name is not randomization. The journal rejected the author's use of the term "a randomized study" in the title and methods. Sadly, the project fell down the EBM pyramid, and was rejected for publication in the journal.

Ariel's initial study plan, a multiple choice test after exposure to the simulation, suffered from many biases. Firstly, there was no comparison group. Secondly, as her plan was to create the multiple choice test herself, the test instrument would be biased with no proven validity or reliability.

Revising her initial plan, Ariel decides to perform a randomized controlled study. She will use a proven randomization procedure to create two groups of students: one group will receive a day of training on the simulator, and another will receive a day of training in the operating room. She will then test each group's performance during a simulated crisis by evaluating their team performance using a validated assessment tool: the Ottawa Crisis Management Global Rating Scale. She reviews her plan with the statistician who will be doing the data analysis before collecting any data and fills in some sticky notes into box 5 of her canvas.

6. Get Consent (Yes, You Need to Get Consent)

Ariel moves to box 6: Data. Here she will detail what data she needs to prove her objectives and how she will get it.

Data access can be one of the more frustrating experiences for researchers, particularly early-career researchers, who have yet to experience the pain of misinterpreting access permissions. Over the past twenty years, I have witnessed the evolution of increasing rigidity of data permission. Using data from human beings - students, patients, colleagues, or random strangers in the street - requires their consent. And, in most cases, requires departmental ethical approval. I have seen many Master’s Degree thesis proposals abandoned as the student overestimated the right to access the data for research. Perhaps the most common mistake is assuming that having the permission to see the data implies that you can use the data for research. Having access to data for teaching, clinical duties, or quality control does not imply that you have free access to do research.

In her initial study proposal, Ariel felt that obtaining the data was easy. She would simply evaluate each student, and the evaluations would form her data. Since she was the instructor for the simulation, she would have the right to see the data. Unfortunately, Ariel is wrong. Having access to data for teaching purposes, or even for teaching quality control, does not mean she can use the data for research. She will need to obtain consent from the students - before they complete the simulation exercises - to be part of her research study.

Ariel updates her canvas. She writes a sticky note detailing data source, how she will get it, and what it will be used for. With ruthless precision, she cuts out any data that does not help her study objectives - there is no point in obtaining data that will not be analyzed. One of her team members is tasked with looking at the University website for a consent form template for her study. Another team member is tasked with completing the hospital ethics approval.

Wrapping Up the Canvas

At this point, Ariel has done all the heavy lifting associated with her project. She can complete the final boxes of the study design canvas: Research Team, Costs, and Revenue, by following the instructions on Using the Research Study Design Canvas .

Ariel now has the backbone of a great simulation study. One of the most important features of design canvases is that they are fluid documents. She can hang the canvas on a wall where all the team members can see it. Research projects often change with development as team members come and go, or data sources change. With the Research Study Design Canvas, she can simply change the sticky notes as the project develops. Her canvas will always show the current best plan.

And, by simply following these six simple steps, she is well on her way to the perfect simulation study.

Want a quick summary of this post? Download the Six Steps to the Perfect Simulation Study Infographic. Are you using the canvas for your simulation research project? Let us know on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. We would love to hear about your study.

Are You Ready to Increase Your Research Quality and Impact Factor?

Sign up for our mailing list and you will get monthly email updates and special offers.