Six Tips for Better Research Ethics

March 22, 2021, 8:30 a.m.

Mention the word ethics to a researcher, and it is quite probable that you will hear a groan, or at least get a raised eyebrow. For many researchers, ethics has become an unwelcome obstacle that appears to rise from nowhere and stands between the researcher and the research. Sadly, many of us did not get the best education in ethics. We often struggle to understand why ethics is important, what the ethical approval process is like, and the purpose of the whole issue.

I had the opportunity to speak with Dónal O'Mathúna, Associate Professor at the College of Nursing at Ohio State University. We had a chance to talk about the role of ethics in research. He dispelled many myths about ethics and offered six excellent tips on how researchers can integrate the concept of ethically sound research into their projects right from the start.

1. Ethics is More than Just Review

"Whether you are a researcher or an innovator, ethics is not just about ethics approval," professor O'Mathuna states. He describes that getting started with ethics starts long before filling out forms for your institutional review board. Ethics should permeate all phases of the research cycle, from idea, to study design, to data acquisition, to publication. "Ethics is primarily about doing things right or wrong," he explains. Ethical approval is not just another hurdle for researchers to tackle. Professor O'Mathuna firmly believes that considering ethical principles throughout your study design and implementation will improve your research and give it a greater impact.

My experience with the ethical approval process started very poorly. For my first research projects, I had very little guidance on how to complete the ethical approval process, and I found it overwhelming and complicated. I failed to see the importance of the extremely detailed form which had box after box of form fields. It was not until I finished my statistics training that I truly understood the process.

For example, many ethical approval forms require a sample-size calculation. In my early research I thought of this calculation as a useless and tedious exercise designed only to stop me from doing my project. Now, I understand, that sample size calculation is not about ethics approval, it's about doing things right or wrong. It is wrong to conduct a research project where the sample size is too small: the participants are exposed to a treatment where there is little hope that the study will be able to prove an effect. In the opposite sense, it is wrong to conduct a research project where the sample size is too large and participants are unnecessarily exposed to a treatment when a smaller sample size would suffice. Sample size is only one example. Defining the population, obtaining consent, maintaining privacy, and specifying the statistic design are not in the ethics form to simply be a hurdle: they are about doing your study right or wrong.

2. Ask Yourself Why

Professor O'Mathuna advises researchers to ask themselves the question "why should this research be done?" This is important as research can entail risks for the participants, but also, often, for the researchers themselves. Especially in the field of disaster medicine where Professor O'Mathuna often works. Research also requires resources, and he recommends that researchers carefully consider their studies to determine if the project is a valid use of resources. He also advises to think about the timing. "Does it really need to be done now?" This has been a common theme over the past year as researchers around the world are faced with prioritizing research goals during the current pandemic.

In a truly inspirational speech Tony Redmond from the University of Manchester - former president of the World Association of Disaster Medicine - described the crux of the ethics of disaster medicine: "Good intentions are not enough." Although he was speaking in particular about disaster medicine relief missions, I feel the same is true of research. Good intentions are not enough. Researchers must ask themselves the more profound question of what the true objectives of the research are. I consider that researchers asking themselves "what am I trying to prove," is always the best first step to a project. Both for ethical and logistical reasons. It is impossible to set up a sound methodological design for a research project without first knowing precisely what you are trying to prove. And without a sound methodological design it is impossible to weigh the costs and benefits of the project. The second question researchers must ask themselves is: "who cares?" Again, without knowing who will benefit from the information and without understanding how it will be used, researchers cannot balance the risks and benefits of the research.

3. Ethics by Design

Thinking carefully about the best way to answer the research question is a fundamental step in developing an ethically sound research project. Professor O'Mathuna advises researchers to ensure that they understand the questions clearly before designing the methodology. Then, to choose the best methodology to answer the question. Whether it is a survey or a randomized trial, researchers must choose the design to match the question, "not just choose the methodology you like to do." Professor O'Mathuna explains that if the design is wrong, it will be hard to justify the use of resources.

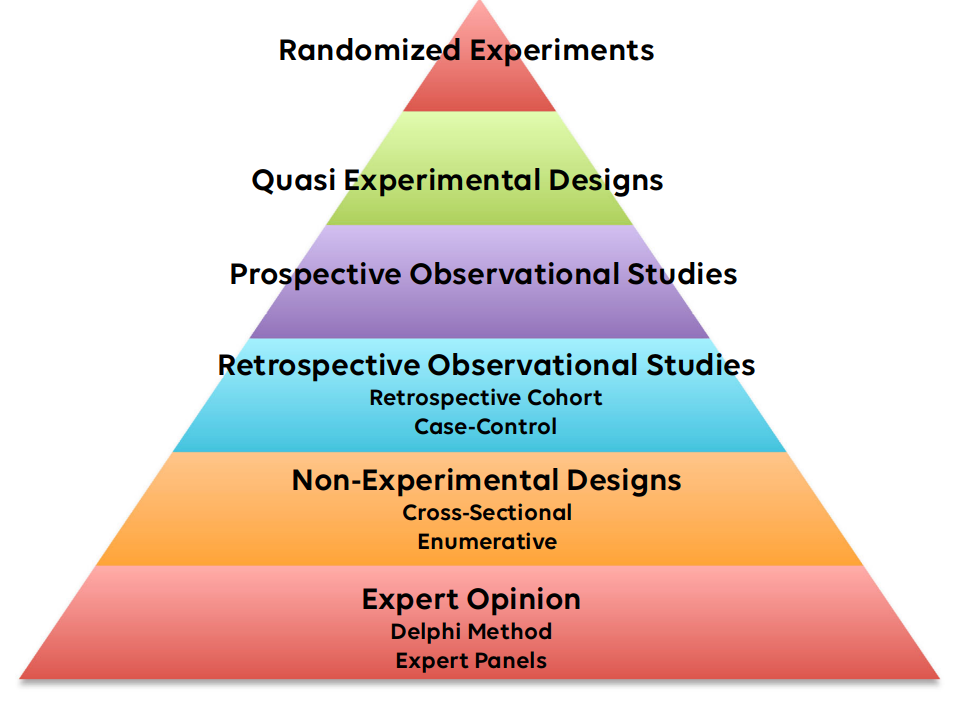

I find that sometimes researchers need to balance the evidence-based medicine (EBM) pyramid against the ethics of the research project. For instance, randomized experiments are at the top of the pyramid. However, randomized experiments are often expensive. In addition, it is often not ethically responsible to experiment until the safety and effectiveness of the treatment has first been shown by observational methods. Researchers should think closely about what the study objectives are and the intended audience and think about what level of evidence would be sufficient to be considered "proof" to the intended audience. For example, convincing clinicians to use a new chemotherapy drug would require strong evidence at the top of the EBM pyramid. Conversely, convincing educators to try a new teaching style for instructing staff members on the departmental cybersecurity plan may require only weak evidence at the bottom of the pyramid. Wasting resources on a more complicated and expensive research design when a less costly design would suffice may not be ethically defensible.

4. Involve the Stakeholders

Involving the stakeholders in research design has not always been the standard. Professor O'Mathuna explains that engaging the participants in the study design has only been well addressed in the past decade. He feels that early engagement with the community where the research will be done can make the study design phase much more effective. For example, community members may be able to warn you in advance about possible ethical challenges such as fear and expectations among the participants. Professor O'Mathuna gives an example of research done in refugee camps where it is important to ask the participants initially: "is this issue important to you?" The most effective research will surround topics that engage the participants. When a topic is genuinely important to the participants, they will want to participate. Measuring stakeholder expectations early on is also important. He warns that "participants may be thinking 'you will get me access to certain treatments I might not otherwise have.'"

I have certainly noticed the change in stakeholder engagement over the course of my career. In emergency medicine research, projects now often involve engagement with patients right at the inception phase of the study when researchers are still setting out the objectives and settings of the study. This was relatively unheard of 20 years ago. I am pleased to see that most of the disaster medicine projects I have worked on recently have been targeted initially to involve the local stakeholders. This includes engagement with the local participants, of course, but also local researchers and local institutions. It is - for the most part - now considered unacceptable for researchers to come from "outside" to study a population without first involving local participants and local researchers in the design, implementation, and analysis phases of the research.

5. Ethical Distribution of Results

Ethical research does not end when the last data is collected. Instead, researchers have an ethical responsibility for the distribution of the results, Professor O'Mathuna explains. Firstly, researchers have an ethical responsibility to inform the participants of the results. In addition, researchers should be clear about the impact of the project: will it change policy? Pave the way to a new intervention? Identify new and important concerns? Professor O'Mathuna cautions that the participants may not always be happy with the results of the study. Hopefully, early stakeholder engagement with clarity of the role of the researcher will mitigate this disappointment. Distributing the results to the participants is also a great way to encourage future collaboration.

A tip that I got from one of my colleagues, Professor Samina Ali, and detailed in a recent blog post is that it is unethical not to publish study results. I also believe that as a community, we are seeing the advantages of the publication of what are often called "negative studies." Knowing what other researchers have tried, what they have found, how they have investigated, and even how they have failed can be valuable information for researchers. Luckily, publishers appear to be noticing the value of these studies, and we are seeing an increasing number of studies published where high-quality studies have failed to prove their hypotheses.

6. Keeping Confidentiality

Professor O'Mathuna advised to be meticulous about the promise of confidentially. Obviously, privacy is important. But sometimes promising confidentiality can be harder than actually keeping it. He gives the example of a researcher who promises that the names of study participants and the location would be anonymous, but later gives sufficient detail in the report that it becomes obvious who the participants are.

As a statistician, I see this issue frequently in survey design. Many researchers use survey tools to gather information that might not otherwise be available. Often researchers are not completely clear on the objectives of the study when the survey is designed, and out of fear of not getting enough information, researchers add numerous demographic questions such as age, location, gender, level of education, employer, and others. Answers to these questions can quickly combine to provide enough information to identify the participant. I urge researchers to first identify precisely the objective of the survey, and then, to cut ruthlessly from their surveys any questions that are not vital for answering the objective. And, following best-practices for survey design , demographic questions should always be optional for the participants.

Putting Ethics First

I have had the privilege to hear professor O'Mathuna teach ethics at the European Master in Disaster Medicine course. His passion for the topic is contagious. The level of engagement of the students in his small-group exercises on ethical issues is impressive. I still remember vividly his explanation of the role of virtue ethics, and the importance of not just obeying the rules but also being the right person.

In my early career I had an irrational fear of the ethics review process. I feared that even though I had designed a perfect study protocol, that the ethics review panel would refuse it due to some "red tape." Now, however, I realize that what I thought was "red tape" is actually the realization of important ethical concepts. And, more than anything, the ethics review process is there to ensure that the research project really is the "best" it can be for all involved: the researchers, the participants, and the audience.

If you are designing a research project, and it will need ethical approval, keeping the six key points that Professor O'Mathuna discussed here in mind will go a long ways to making sure your study gets quick approval. In addition, you may start to perceive the ethics review as an opportunity to improve your research, not just another hurdle.

If you enjoyed this post, please sign up for our mailing list to keep up to date on new topics as we write them.

Are You Ready to Increase Your Research Quality and Impact Factor?

Sign up for our mailing list and you will get monthly email updates and special offers.